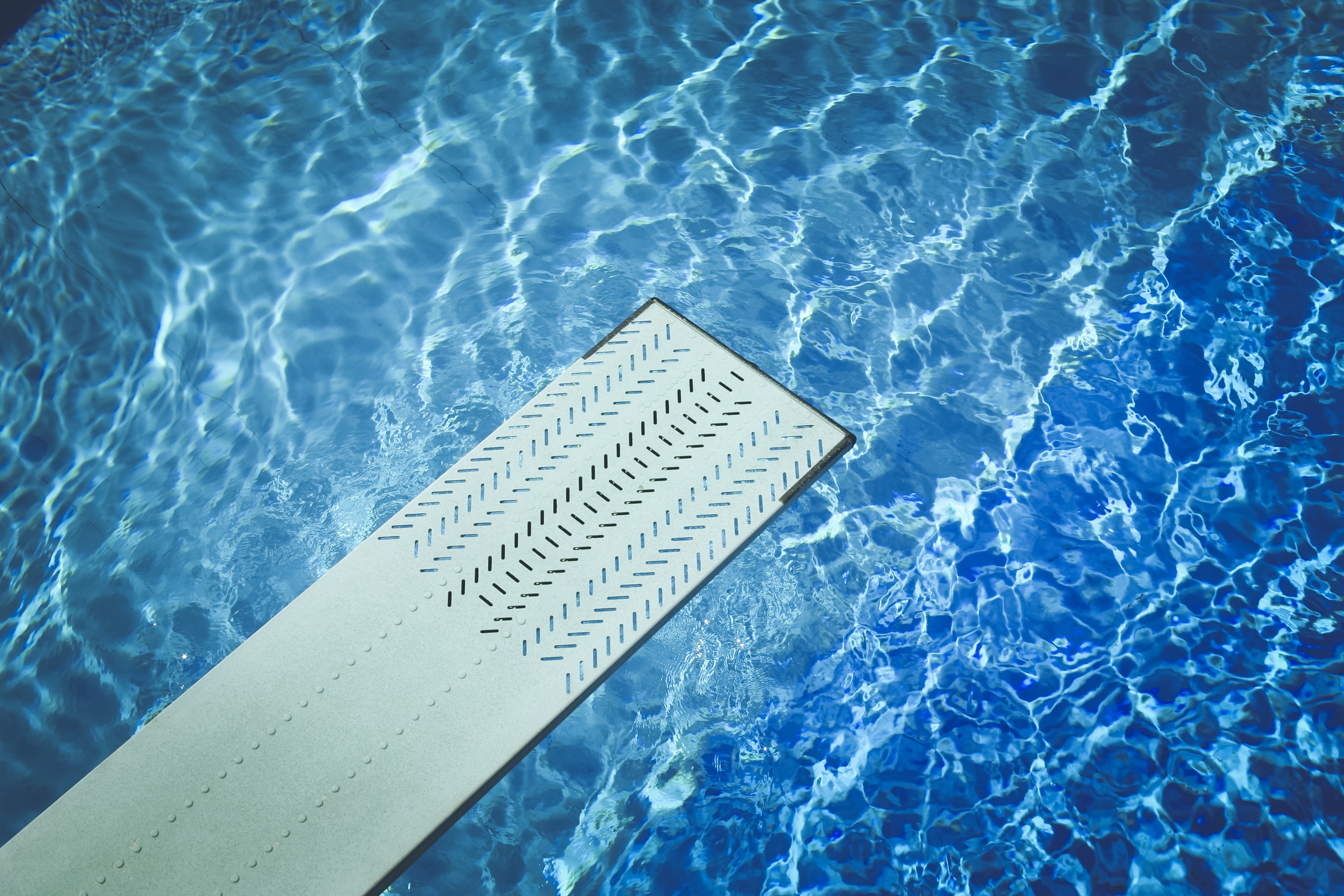

Marathon runners and novelists share one thing in common. They both have to deal with “hitting the wall.”

Although I ran cross-country in high school (I was terrible), I have never run a marathon. But from what I understand, marathon runners often hit a wall anywhere from around mile 15 to mile 20—somewhere past the mid point.

By mile 15, you have depleted your glycogen stores, which were built up from whatever you ate before the race. Suddenly, your body is breaking down muscle and fat tissue, and your mind is beginning to fog up. Fatigue hits you like…well, like a wall.

This description sounds an awful lot like a writer at the midpoint of a novel. For writers, ideas are our glycogen stores, and when we hit the midpoint of our novel, we often find ourselves sorely lacking in fresh ideas. We may have gotten off to a quick start and we may even know how we want to end the novel, but we’ve run out of good ideas to carry us through the murky middle.

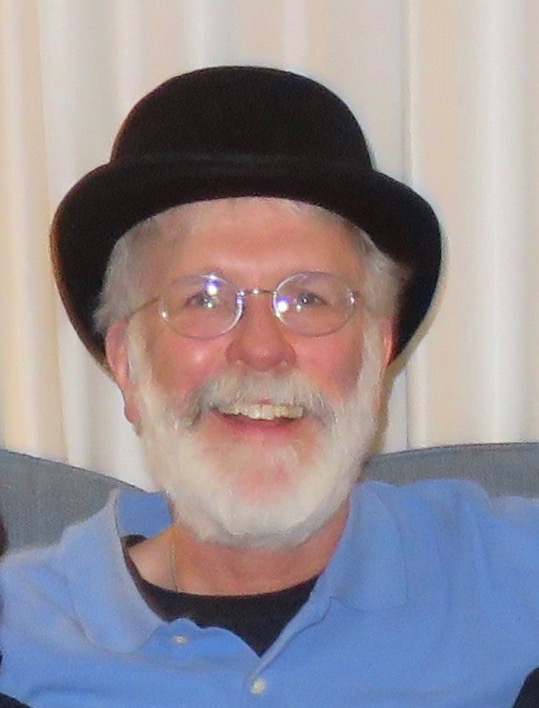

In fact, this happened to me recently. I had plenty of good ideas that carried me about three-quarters of the way through my novel—and I have a pretty good idea how I want to finish the story. But I have hit a wall. The ideas are used up, and my brain is beginning to fog. This is where a lot of runners—and writers—are tempted to toss in the towel.

In fact, this happened to me recently. I had plenty of good ideas that carried me about three-quarters of the way through my novel—and I have a pretty good idea how I want to finish the story. But I have hit a wall. The ideas are used up, and my brain is beginning to fog. This is where a lot of runners—and writers—are tempted to toss in the towel.

For runners, one recommendation to deal with this problem is to refuel your body throughout the race with water, Gatorade, or carbohydrates before you hit the wall. If you wait until you hit the wall, you’re in for a lot of pain.

It’s the same with writers. If you look ahead and see that your ideas are running thin, don’t want for the pain to set in. Stop what you’re doing, brainstorm, replenish your ideas, and then do a little more outlining before moving forward.

I like to meet a daily writing quota, so the idea of stopping the process to do more brainstorming and outlining is frustrating; it feels like I’m going nowhere. So I have to force myself to take the time necessary to replenish my ideas—but it pays off in the long run.

Another tip that trainers often give to runners as they approach the wall is to interact with spectators along the route. This might be something as simple as waving, talking to spectators, or giving a thumbs-up. Some sports psychologists also suggest having a running buddy with whom to interact. All of this interaction has the dual benefit of distracting you from your pain and giving you the encouragement you need.

Again, writers can borrow this advice. When you hit the wall, turn to others for help.

Many of us are attracted to writing because it’s a solitary sport, and you like working alone. But there are points when you need somebody that you can bounce your ideas off of. You need a little help from your friends.

The good news is that if you keep pushing, keep brainstorming, keep outlining, and keep bouncing ideas off of friends, you might find yourself moving into what runners call the “final kick.” A runner’s body, which only miles ago verged on giving up, will suddenly summon up newfound energy in the final few miles of a marathon. Likewise, a writer who felt like giving up only a half dozen chapters earlier will kick into high gear, and the ideas will start coming fast and furious.

So stick with it, and you’ll find it worth it in the end as you cross the finish line and put the last period on the last sentence of the last paragraph of your novel.

Then, just like a marathon runner, it’s time to collapse. And celebrate.

* * *

5 for Writing

- Get writing. Find the time to write. Then do it.

- Learn by listening—and doing. Solicit feedback, discern what helps you.

- Finish your story. Edit and rewrite, but don’t tinker forever. Reach the finish line.

- Thrive on rejection. Get your story out there. Be fearless. Accept rejection.

- Become a juggler. After one story is finished, be ready to start another. Consider writing two at once.