by Sandra Merville Hart

Historical novelists research ways of life, events, fashion, and a myriad of other topics. Another aspect of writing to consider is dialogue. Should we use contractions in our characters’ conservations?

Whatever we think, it is also important to consider our editor’s opinion. He or she might believe that the dialogue should be liberally sprinkled with contractions because readers will relate to it. Others may feel contractions weaken the historical authenticity.

I decided to pull a variety of novels written in earlier eras from my bookshelf to verify the use of contractions in dialogue. The results surprised me.

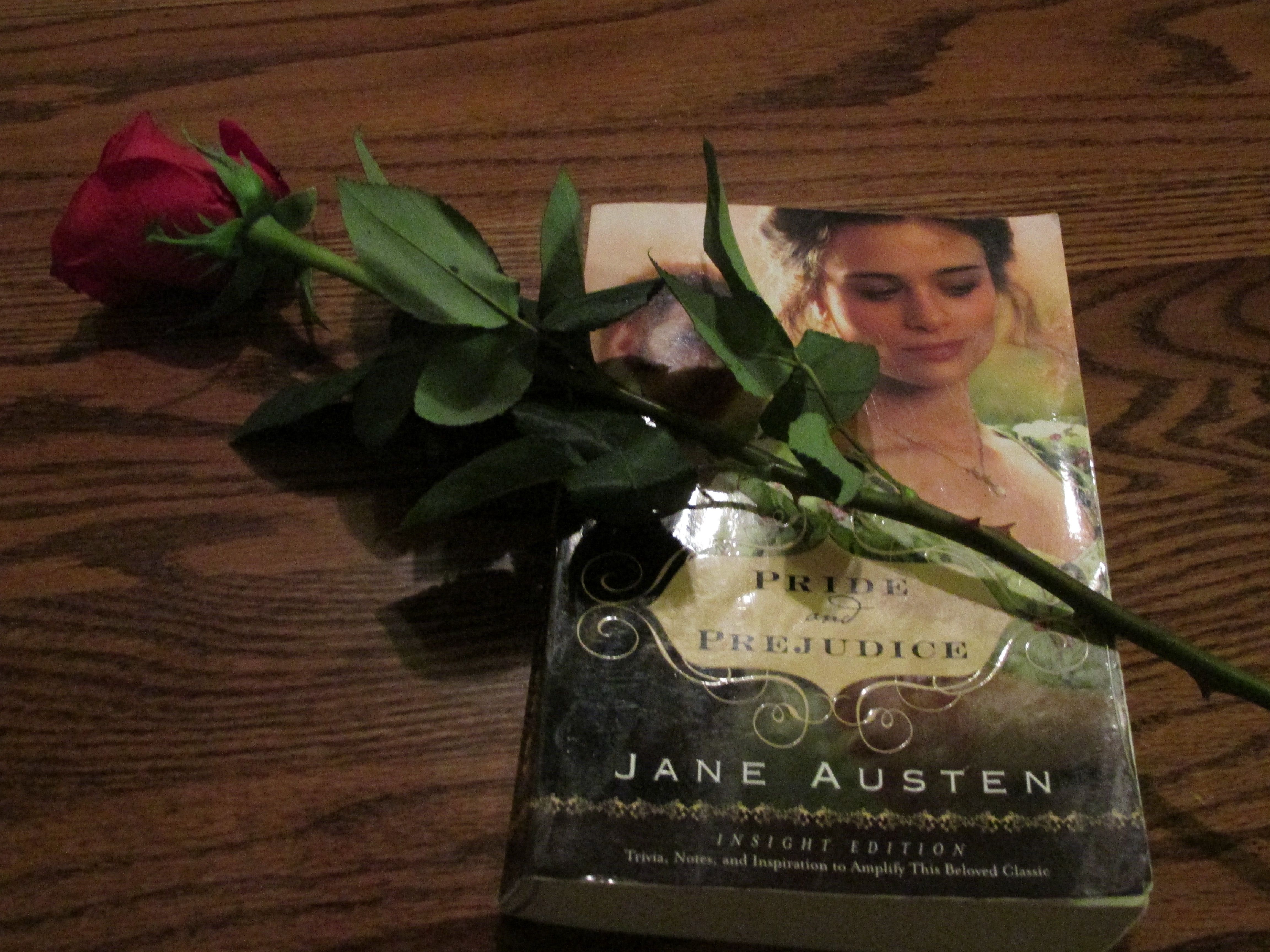

I didn’t find any dialogue contractions when leafing through Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. I didn’t reread the story, but this novel, published in 1813, contains few—if any. [bctt tweet=”Use #dialogue contractions in historical novels to enhance character’s style. #writing #histfic ” username=”@Sandra_M_Hart”]

Mark Twain published The Innocents Abroad in 1869. This novel is a narrative with little dialogue yet those conversations contain contractions. His book about his adventures in the western territories of the United States, Roughing It, has a lot more dialogue with contractions. Twain’s novels, Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer, utilize contractions. They feel authentic.

Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables published in 1908. Montgomery used contractions in conversations.

Great Expectations, the classic novel by Charles Dickens, published in 1861. This master storyteller sprinkled contractions throughout his dialogue.

Ernest Hemingway published The Sun Also Rises in 1926. He also uses contractions in dialogue.

The only author of the five who didn’t use contractions is Jane Austen. Her writing has a formal feel, yet her dialogue still flows naturally.

Writers may be more influenced by Jane Austen’s style, choosing to write dialogue without contractions. Reading conversations aloud will show where to soften and tweak the wording. Writing without contractions may feel more authentic.

Other novelists decide to include contractions for every character.

Perhaps there is a happy medium. Don’t shy away from using contractions in historical novels. Don’t avoid them at all costs.

Instead use dialogue contractions as one more way to differentiate a particular character’s style—to add color and flavor and dimension. Some folks speak in formal language while others never do. The way they communicate reveals clues about who they are.

Dialogue then becomes another tool in a novelist’s arsenal for effective communication.