I watched a movie set in the 1800s recently where a child said, “Cool!” He didn’t refer to the temperature; something good happened. The comment jolted me out of the scene because it didn’t belong.

I’m currently reading a novel set in the 1600s. I’ve enjoyed learning about everyday living in that time period. However, the novel contains modern phrases that don’t fit the time period, such as read me like a book. This didn’t fit my perception of the vernacular from three hundred years ago and temporarily took me out of the story.

It’s probably a given that all historical authors will sometimes choose familiar words that don’t belong in the setting, but how can we limit these mistakes?

[bctt tweet=”Avoid a common mistake made by #historical #authors by immersing yourself in books set around your novel’s era.” username=”@Sandra_M_Hart”]

The first way is by immersing yourself in books set near the time period of your novel. For example, when researching the American Civil War, I started by reading soldier accounts. These informative transported me to battlefields. Diaries written by slaves, Southern wives, and Northern abolitionists demonstrated beliefs and opinions as well as words used to express themselves. These gave the civilian perspective. Novels such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Little Women, and A Man Without a Country are just a few of the books that taught me the faith and values that people held dear.

Become a detective while enjoying novels written during the time period. Read between the lines. For example, contemporary writers rarely describe phones because we all know what one looks like and its function. The same thing is true of books written two hundred years ago; everyday objects such as oil lamps are rarely described so read as if you are a detective searching for clues.

Another great tool at an author’s fingertips is the Online Etymology Dictionary. This dictionary shows the meaning, origin, and the approximate year a particular word began to be used.

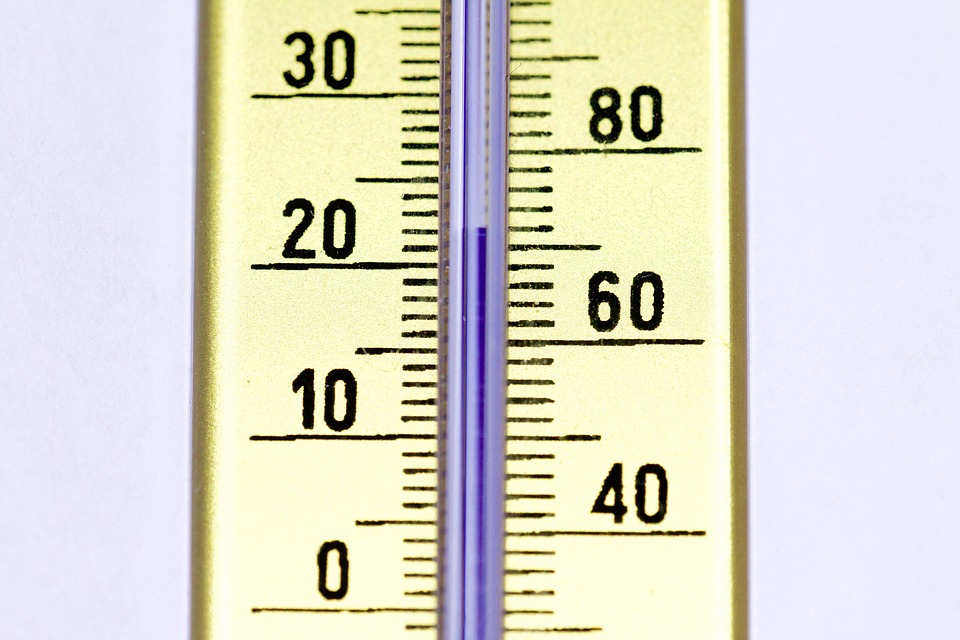

For instance, some probably imagine the word cool started to refer to something other than temperature in the 1970s. The link above shows the word started to mean general approval in the 1940s, possibly earlier than expected.

We often say sure in our contemporary novels. This word has actually been in use for a long time. Charles Dickens used the word in A Christmas Carol, making it safe for me to write it in my Civil War novels. Checking the Etymology Dictionary shows that sure as the affirmative yes began around 1803. Sure thing is another term often used in historical novels – this is correct if your novel is set in 1836 or later.

An online source for the origin and meaning of phrases if a great writing tool. This link contains lists for Phrases coined by William Shakespeare, Phrases first found in the Bible, and Famous Last Words – to name a few. These are interesting and fun. While searching for a particular phrase, you may find a different one that fits even better.

I didn’t find the date that read me like a book came into usage. Well-read is surprisingly from the 1590s and reread as a verb began in 1782. This site is such a gift to authors.

When writing a word or phrase in your historical novel that an editor or critique partner questions, click on these links and dig deeper.

Chances are you and your critiquer will both learn something.