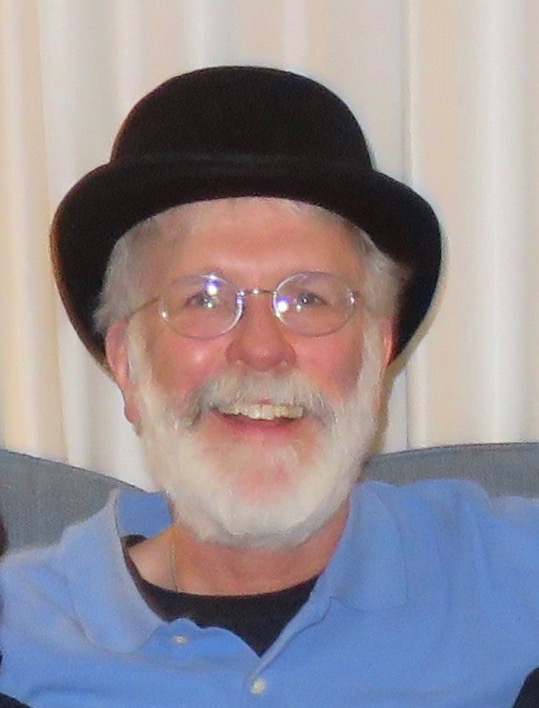

Doug Peterson (right) with Jurgen Litfin, brother of the first person shot trying to escape into West Berlin.

NOTE—Doug Peterson’s previous blog, Do Your Research Right When You’re Writing Historical Fiction, discussed his research habits. This is a follow-up to that blog.

I guess I should have known what day it was when I showed up at the old watchtower in Berlin in 2011. I didn’t realize that I was arriving there on the 50th anniversary of the death of Gunter Litfin, whose memory was being honored by this very watchtower—a tower that had once been used by East Berlin guards with shoot-to-kill orders.

Back in 1961, Gunter Litfin became the first person to be shot by guards while trying to escape from Communist East Berlin into free West Berlin. Gunter was killed while trying to swim across a canal, which was located not far from this very watchtower.

When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989 and Germany reunified, Jurgen Litfin, the brother of Gunter, had the watchtower preserved as a museum in his brother’s honor. But because I showed up on the 50th anniversary of Gunter’s death—to the day—I found that the watchtower was closed in his memory.

But I didn’t give up. I was in Germany for a week doing research for my Berlin Wall novel, The Puzzle People, so I came back to the watchtower the next day. This time, I found a decent-sized crowd milling around, but no one was being allowed inside the watchtower. Standing in front of the tower was a stern-looking, elderly German man, whom I learned was Jurgen Litfin.

“Why isn’t he letting anyone inside?” I asked a woman.

“I don’t know,” she said, “but he kind of scares me.”

When I approached Litfin, I found that he didn’t speak a word of English. So, with a German man translating for me, I explained that I was writing a historical novel based on the Berlin Wall, and one of my key scenes takes place in a watchtower just like this one.

To my amazement, he allowed my wife and I—and no one else—into the watchtower. So we climbed up all three levels, and I took photographs and videos like mad.

The reason I bring up this story is that my visit inside the watchtower led me to completely revise the climactic scenes of my novel, The Puzzle People. This experience also taught me about the importance of visiting the location of your novel when doing research. Of course, some budgets will not allow visits to exotic locations, but all of my other historical novels have been located in the United States, where on-site visits are much more economical. So if your budget allows it, by all means visit the location of your story.

But when should you visit? Before you begin writing, during the writing process, or after the novel is completed?

My choice is to go after I have completed a rough draft. That way, I know what locations I need to see. Then I can make revisions based on what I saw on location, as I did with The Puzzle People. Although my watchtower scene needed some heavy reworking, in most cases a visit to the location does not require me to make drastic changes.

Last year, when I finished the rough draft of a novel based in New Orleans during the second year of the Civil War, I went to the Big Easy with a list of locations that I wanted to see and photograph. If you give talks about your novels or historical subjects covered in your stories, the photographs you take have the added benefit of providing you with plenty of visuals to use in these presentations.

But before you visit the location in person, I suggest you make some “virtual visits.” The Internet today makes it possible to get a lot of the on-site research done from the comfort of your own office. Google Earth now makes it possible to walk the streets of European cities, without having to buy an airplane ticket and take one nibble of airplane food. So if your budget doesn’t allow a trip to a foreign country, take a trip with Google Earth.

Studying the location of your story is like buying a house. It’s a good idea to explore houses online before going out and seeing them in person. But you wouldn’t buy a house without ultimately going to the home and walking through it and hiring an inspector.

It’s the same with a novel. Check out the setting online, and then visit in person—if you can. At the very least, you’ll get a nice vacation out of it.

* * *

5 for Writing

- Get writing. Find the time to write. Then do it.

- Learn by listening—and doing. Solicit feedback, discern what helps you.

- Finish your story. Edit and rewrite, but don’t tinker forever. Reach the finish line.

- Thrive on rejection. Get your story out there. Be fearless. Accept rejection.

- Become a juggler. After one story is finished, be ready to start another. Consider writing two at once.

No Comments