Combatting the Noise Issue

By Sandra Merville Hart A few family members came over to watch a movie this weekend. The dramatic…

February 24, 2017

By Sandra Merville Hart A few family members came over to watch a movie this weekend. The dramatic…

February 24, 2017

By Sandra Merville Hart It happened again. Somewhere in the middle of writing the novel, the story got stuck…

January 21, 2017

By Sandra Merville Hart Somewhere in the midst of writing my second novel my story started to get…

December 21, 2016

by Sandra Merville Hart Mark Twain’s life was at a pivotal moment in the 1860s. He was out of…

November 21, 2016

Historical authors can glean a wealth of information from old photos. They give an unintentional glimpse into everyday life…

November 19, 2016

I watched a movie set in the 1800s recently where a child said, “Cool!” He didn’t refer to the…

October 21, 2016

by Sandra Merville Hart Two months ago we talked about the author of Charlotte’s Web, E.B. White, and…

August 8, 2016

Researching for a story or article can be a chore. It’s certainly a lot of work to dig for…

January 13, 2016

With Christmas just around the corner, I decided to read Charles Dickens’ famous novel, A Christmas Carol, and discovered…

December 12, 2015

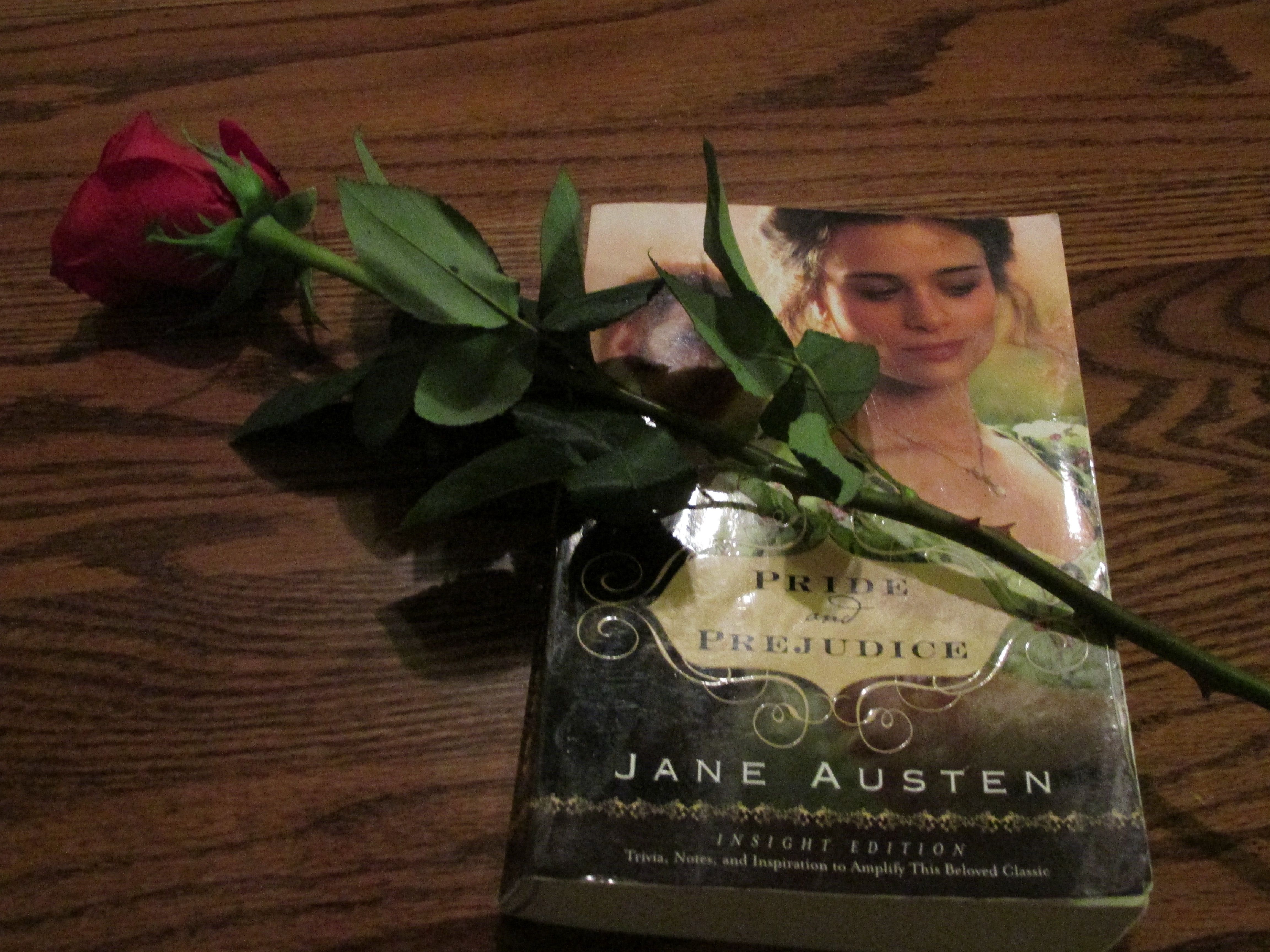

By Sandra Merville Hart I’ve read Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice at least a dozen times and loved…

November 14, 2015