Details, Details: How to Write a Rich Setting for Your Story

It’s incredibly exciting to have a new story idea. The characters develop in our mind and seem to be…

December 27, 2022

It’s incredibly exciting to have a new story idea. The characters develop in our mind and seem to be…

December 27, 2022

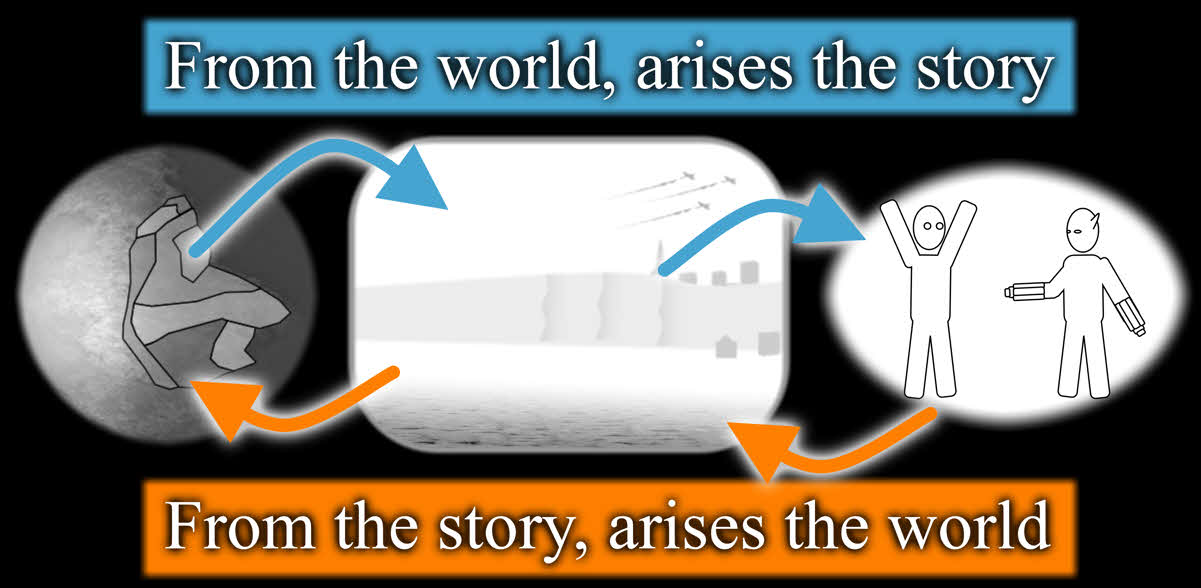

The story setting in literature describes the where and when of a character and action. The setting of a…

April 25, 2021

Well, it took God six days to complete the one you’re living in, so don’t expect to make yours in one day.

Worlds are complicated things, and in order to make one believable, you’ll need to take into consideration a whole host of things from politics to geography.

When writing a speculative fiction novel, determine what the things of value are in your world. Water, food, shelter-building resources,…

February 7, 2016

Regardless how fantastic the setting, the people in your book must treat their environment as commonplace. A character who…

November 28, 2015

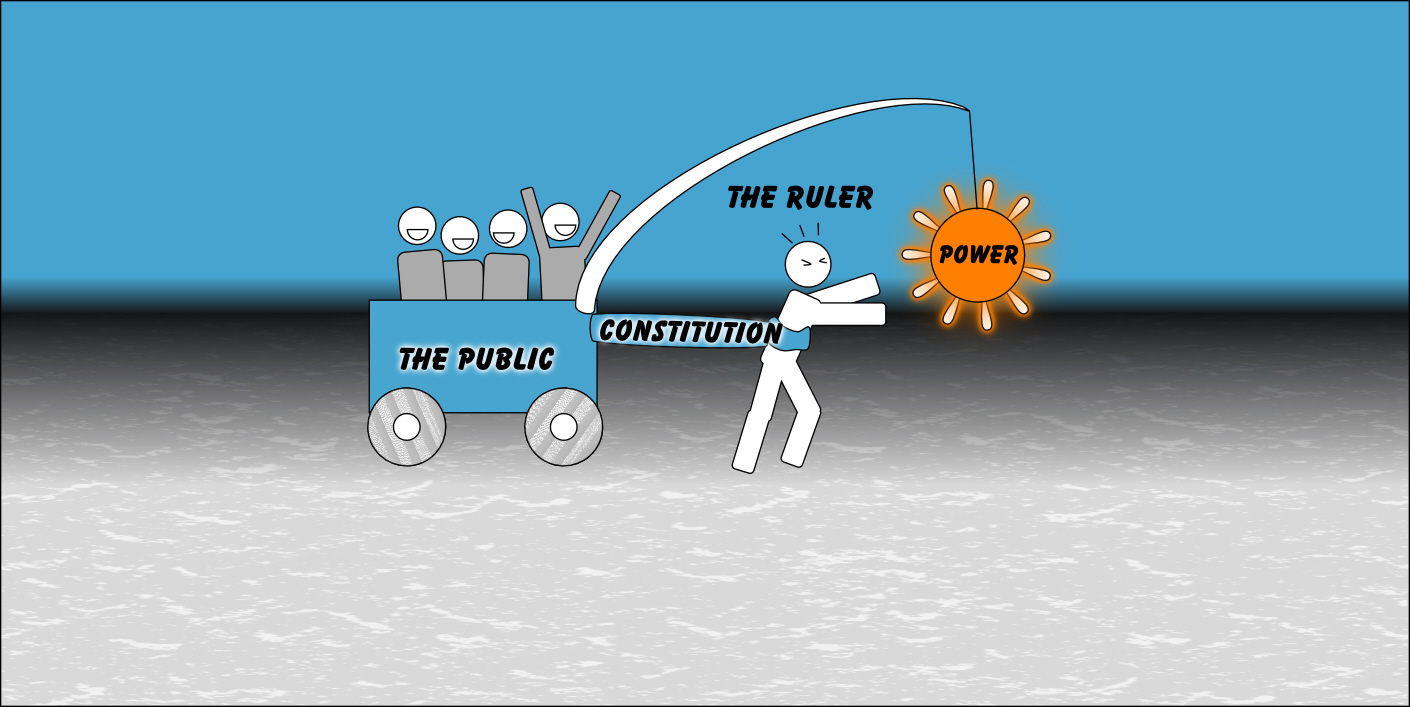

The people in your world need governance. I’m sorry. I wish I could make it untrue, but a believable…

September 5, 2015

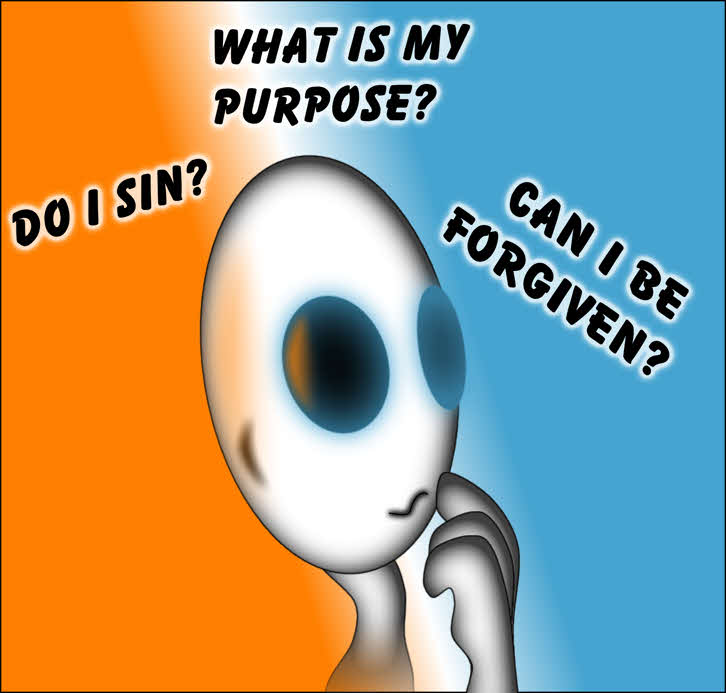

Atheists believe all creatures evolved over countless millennia of bloodshed, allowing only the fittest members of a species to…

July 3, 2015