Pizzanomics and the Economy of Words

In The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde writes that people know the price of everything and the value…

March 10, 2023

In The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde writes that people know the price of everything and the value…

March 10, 2023

Any gamers in the house? I’m a huge fan of games: the creativity, the challenges, and the competition, of…

January 17, 2023

Sharing your fantastical words and worlds can be terrifying. You feel everyone’s eyes on you, weighing the thoughts you…

November 15, 2022

An important part of what makes your story fit into the Science Fiction and/or Fantasy genres is an element…

December 15, 2021

Time travel is a stable in science fiction. Countless books, comics, movies, and TV shows have used it as…

September 7, 2021

There’s an important difference between Science Fiction and Scient Fantasy. Scient Fiction is based on real world science, even…

June 7, 2021

Sometimes it’s easy to think character development looks similar across genres. And for the reader, it usually does. Even…

September 7, 2020

There’s something about a good sci-fi story that pulls me in and doesn’t let me go. In those moments,…

October 7, 2019

The trend within the fantasy and sci-fi genres is to push for more detailed world-building within our stories. While…

May 7, 2018

Which world, or sub-genre, does your novel belong to? Bookstores have general genre sections in which to categorize their…

April 7, 2018

We’ve spoken before about how little details can help color your storyworld. Societal habits, mating customs, dinner choices, and…

August 10, 2017

The autopsy window allowed Jim a clear view of the good doctor’s grim work. The gray-skinned corpse had been…

January 16, 2017

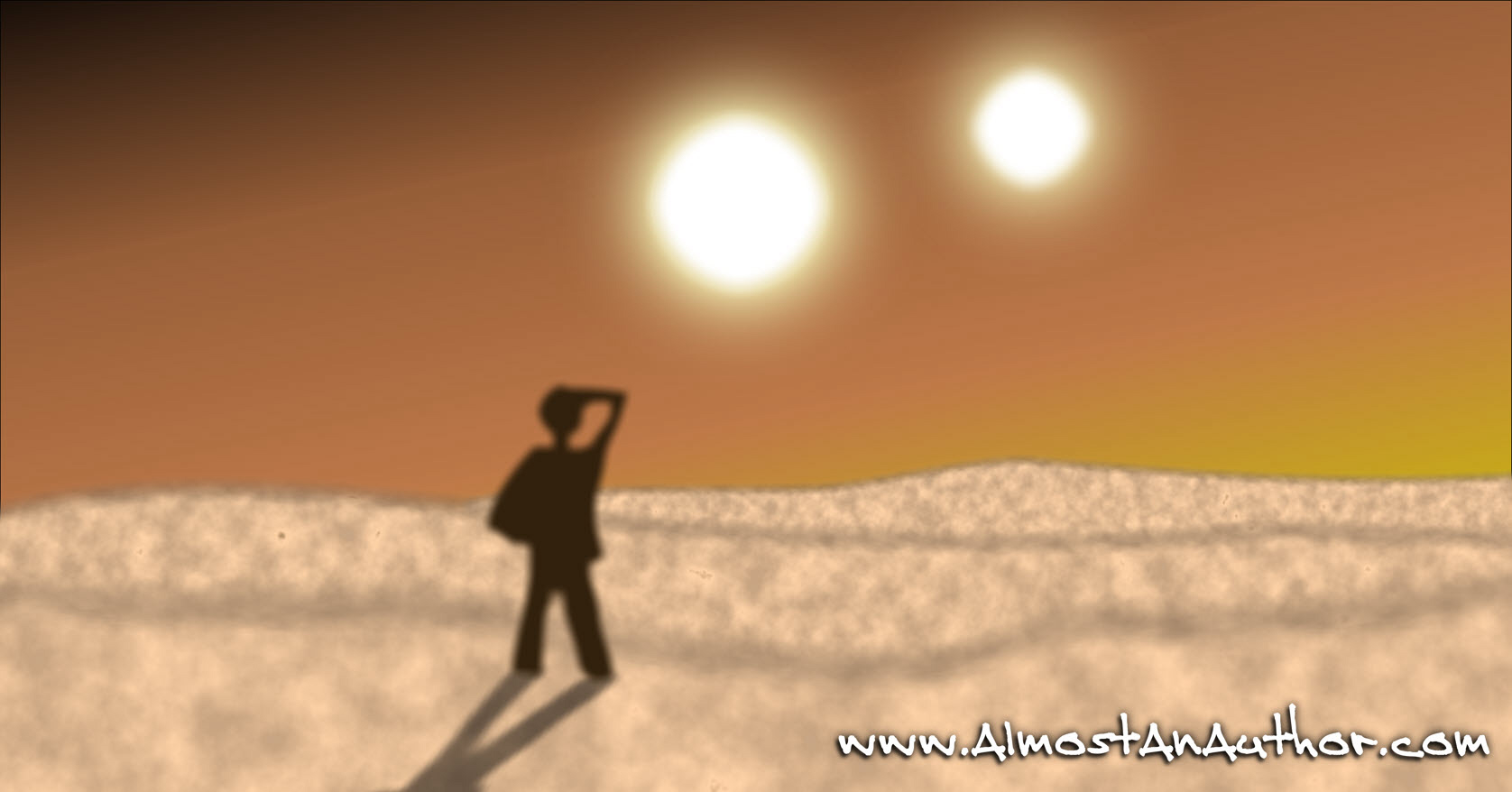

As Tatooine’s twin suns slowly inch to the sand dunes in the horizon, a lone figure strains his eyes…

September 11, 2016