writers chat recap for January part 1

Writers Chat, hosted by Jean Wise, Johnnie Alexander, and Brandy Bow, is the show where we talk about all…

January 15, 2022

Writers Chat, hosted by Jean Wise, Johnnie Alexander, and Brandy Bow, is the show where we talk about all…

January 15, 2022

Many fantasy writers got their introduction to the genre not through books but through Table Top Role Playing Games…

May 7, 2021

Happy New Year, awesome authors! As writers of speculative fiction, military forces are a staple in many of our…

January 7, 2021

As writers of speculative fiction, military forces are a stable in many of our stories. Basing these on a…

December 7, 2020

Can you share a little about your recent book? I just finished the last book in the Ravenwood Saga,…

May 1, 2020

It’s a new year. For some writers it is an opportunity to pick up a previous work that had…

January 9, 2018

Hey guys, I wanted to kick this whole thing off by welcoming you to the ranks. (Though I’m sure…

July 23, 2017

Regardless how fantastic the setting, the people in your book must treat their environment as commonplace. A character who…

November 28, 2015

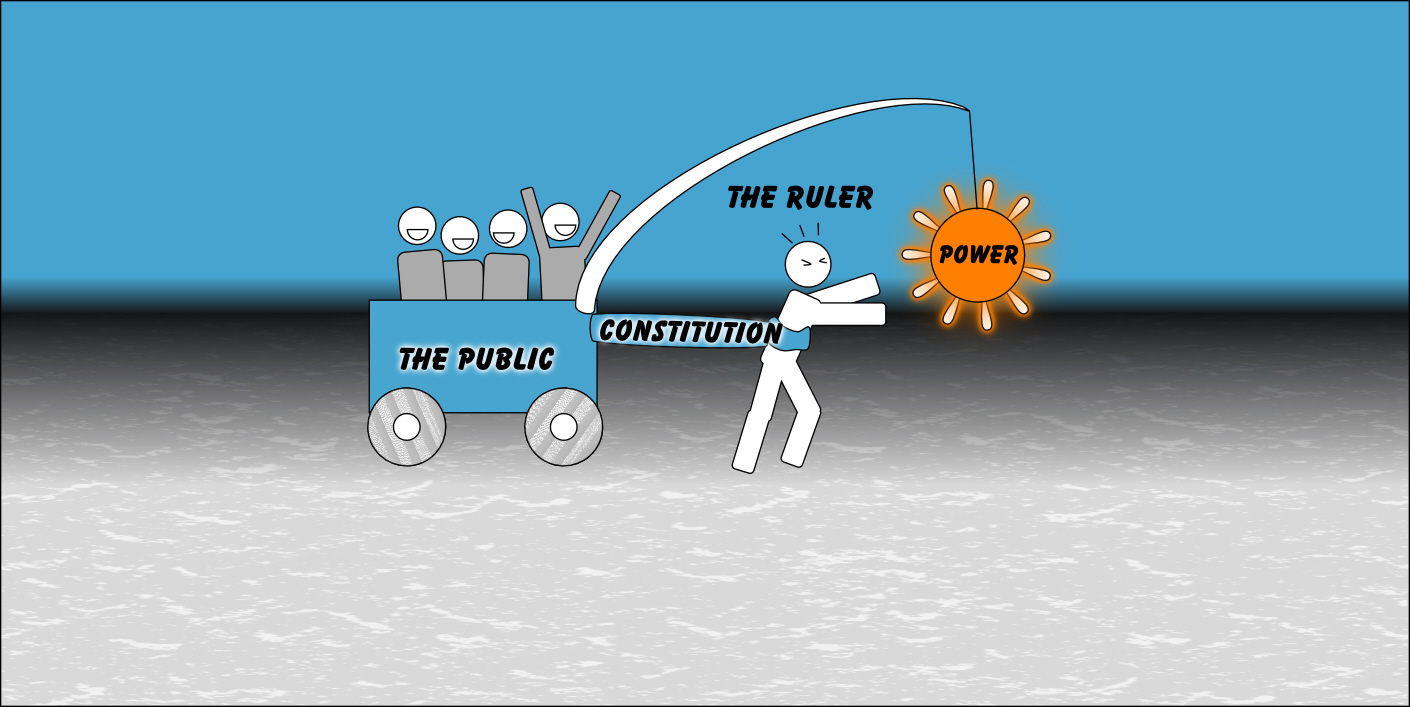

The people in your world need governance. I’m sorry. I wish I could make it untrue, but a believable…

September 5, 2015

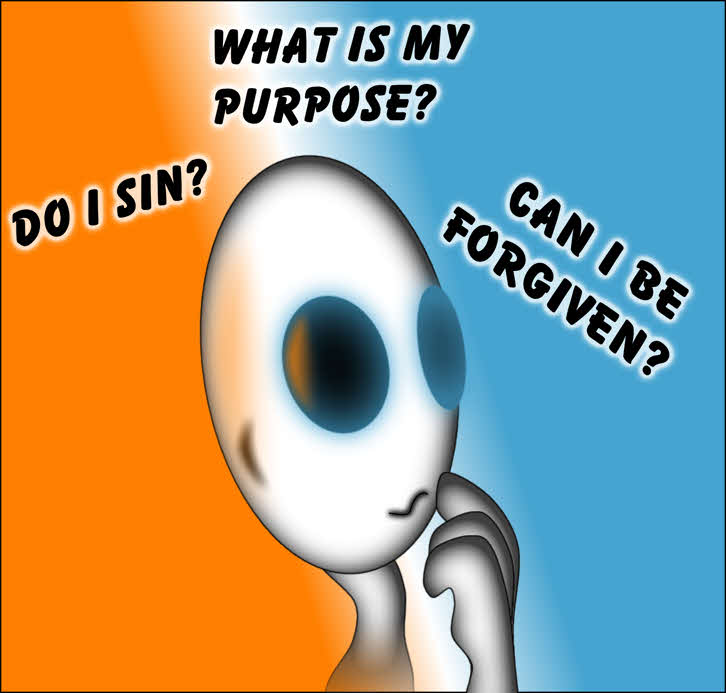

Last month we looked at writing fictitious, sentient creatures within our own universe. In summary, God has a plan…

August 4, 2015

Atheists believe all creatures evolved over countless millennia of bloodshed, allowing only the fittest members of a species to…

July 3, 2015