Wonder

I wonder… What made you fall in love with science fiction and fantasy? As a child, I loved fairy…

October 10, 2022

I wonder… What made you fall in love with science fiction and fantasy? As a child, I loved fairy…

October 10, 2022

Fantasy and science fiction stories can push the bounds of what is possible in amazing ways. We design intricate…

March 7, 2022

Time travel is a stable in science fiction. Countless books, comics, movies, and TV shows have used it as…

September 7, 2021

Happy New Year, awesome authors! As writers of speculative fiction, military forces are a staple in many of our…

January 7, 2021

As writers of speculative fiction, military forces are a stable in many of our stories. Basing these on a…

December 7, 2020

It’s not always easy creating a whole world from scratch. Amy C. Blake agreed to give a few words…

August 27, 2020

Have you ever walked into someone’s house as a first-time dinner guest and felt out of place? Ten other…

July 7, 2020

Writing during a global pandemic is probably not something you thought you’d be tackling. Writing is hard enough by…

June 7, 2020

There’s something immersive about opening a fantasy or sci-fi book and feeling like there were hundreds of pages of…

April 7, 2020

Margaret Atwood is well-known for her novel The Handmaid’s Tale, a dystopian first published in 1985. Her novel covers…

March 7, 2020

When it comes to writing, some of us like to picture it in our head and write what we…

November 7, 2019

Most of us have probably been told to “plunge your main character into terrible trouble as quickly as possible.”…

September 7, 2019

Most Mystery/Suspense/Thriller stories are set in the real world, but the realities of that world cover a wide spectrum…

June 17, 2019

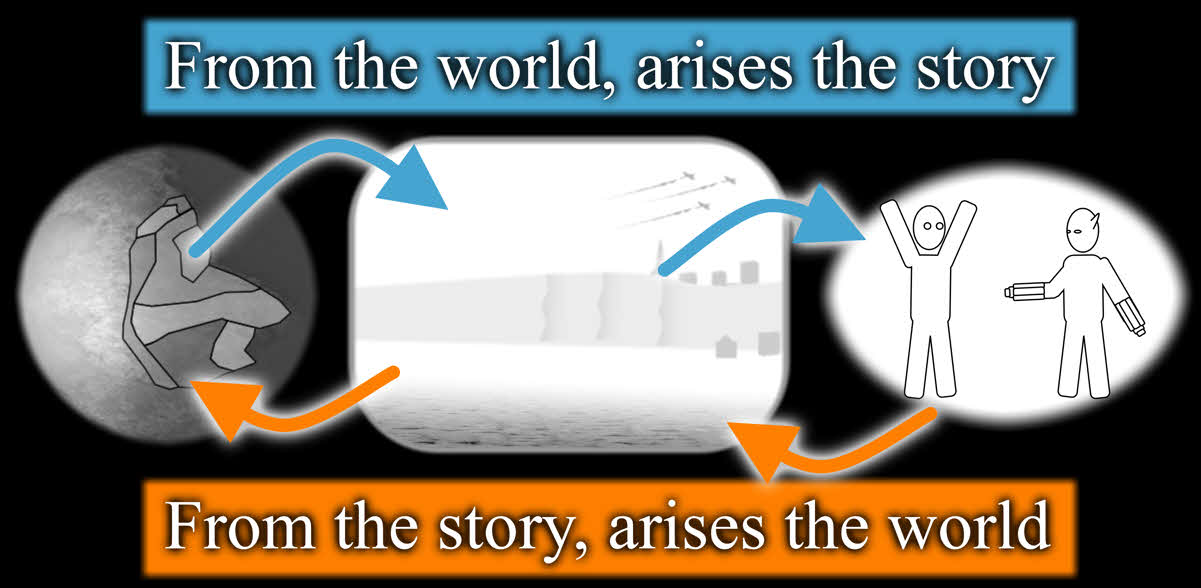

The trend within the fantasy and sci-fi genres is to push for more detailed world-building within our stories. While…

May 7, 2018

Well, it took God six days to complete the one you’re living in, so don’t expect to make yours in one day.

Worlds are complicated things, and in order to make one believable, you’ll need to take into consideration a whole host of things from politics to geography.

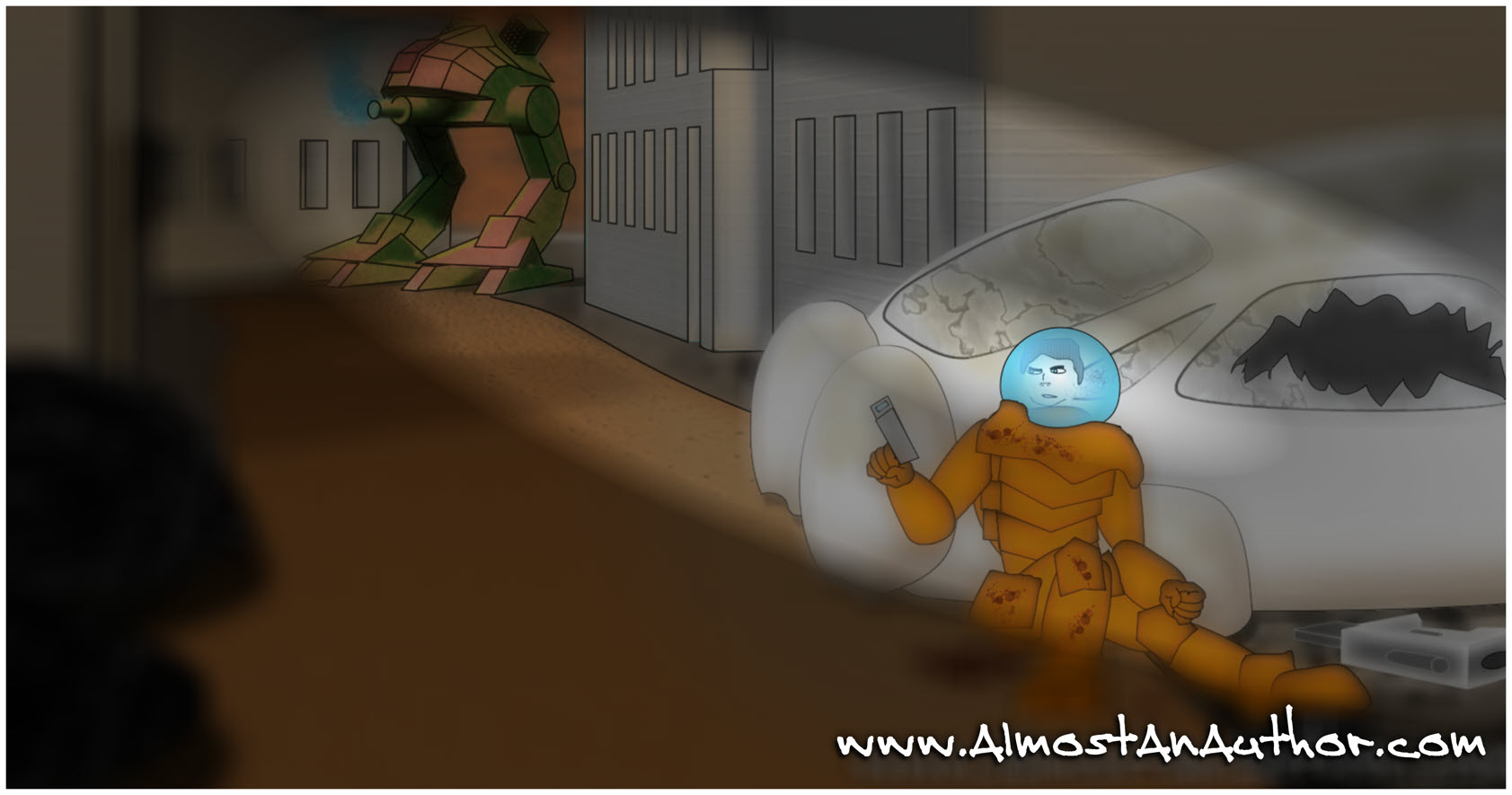

The carbine was still jammed and Jim couldn’t do anything to fix it. He finally tossed it aside and…

November 9, 2016